Memory in Uncertainty: Web Preservation in the Polycrisis

Executive summary

This research evaluates the design of web archival tools and the broader social and political contexts of web archiving tools and practice, both from the systemic realities of web archiving as a practice, and through the context of a specific emergent tool, the Webrecorder open-source project. Through these lenses, this research uncovers threats to the growth and resilience of web preservation tools and long term data storage, driven by systemic factors — inadequate risk assessments by funders, deteriorating geopolitical and ecological conditions, and a lack of collaborative research and knowledge sharing within the practice of web archiving and its related fields.

Digital and web archiving is the practice of curating, collecting, storing and preserving large collections of material on computer systems and networks. Digital archives can be assembled through the production of a digital replica of a real-world object via photography, scanning or other digitisation processes. Web archives are developed partially or entirely from digital objects, such as websites, historical software programs and other products. Within the bounds of the practice's own definition, digital and web archives are created to preserve historical objects,[1] develop cultural repositories, or maintain social history for items deemed to be of public interest. This is only part of the broader range of applications of digital and web archive practices, and while in theory these two disciplines exhibit their own idiosyncrasies, in practice their frontier remain porous, digital archives employing web archive techniques and vice-versa. This internal friction within the broader field of archiving was highlighted by Trevor Owens, Head of Digital Content Management at the Library of Congress, back in 2014:

"One of the tricks to working in an interdisciplinary field like digital preservation is that all too often we can be using the same terms but not actually talking about the same things. In my opinion, the most fraught term in digital preservation discussions is 'archive.' At this point, it has come to mean a lot of different things in different contexts."[2]

This research finds that the field of web archiving and its landscape of tools and institutions are out of step with the realities of rising instability and complexity of the 21st century. As societal digitisation accelerates, so too has the belligerence of state and corporate power, the democratisation and intensity of targeted harassment, and the collapse of consent by communities plagued by ongoing (and often unwanted) datafication. Drawing from the climate of the 2020s and informed by an extensive landscape review, as well as a series of qualitative interviews with digital and web archive practitioners conducted between December 2021 and May 2022, this research identifies key intersectional systemic challenges to the fields of digital and web archiving. Many of these issues threaten the quality and resilience of web archives and the integrity of digitally-archived material. They also have profound implications to the physical safety, legal standing and mental health of archive practitioners and communities subjected to archiving. This research identifies and documents issues of ethics, consent, digital security, colonialism, resilience, custodianship and tool complexity.

Despite the challenges identified in the research, there exist compelling reasons to remain optimistic. Funders and projects committed to addressing web and digital archiving in the polycrisis can explore emergent technologies, stronger socio-technical literacy amongst archivists and critical interventions in the colonial structures of digital systems as immediate points of intervention. By acknowledging the shortcomings of cybernetics, resisting the desire to apply software solutionism at scale, and developing a nuanced and informed understanding of the realities of archiving in digitised societies, a broad surface of opportunities can emerge to develop resilient, considered, safe and context-sensitive archival technologies and practice for our uncertain world. ?

I. Preserving history in the violent present for an uncertain future

How do we save the past in a violent present for an uncertain future? As the new decade lurches forward, general-purpose networked computing faces significant socio-technical and political trials. Long gone are the days of technological optimism; the benefits and opportunities afforded to societies by digital infrastructure and digital culture are marred by serious socio-technical flaws that make the systems we rely upon fragile and ethically compromised. From the subtle psychological influences of digital interfaces that compress our cognitive potential, to the hidden power structures baked into opaque infrastructures, the challenges posed by the digitisation of society are systemic and complex.

2022 has been a remarkable demonstration of how brittle digitised societies have turned out to be. There are countless demonstrations of this fragility, but to list a few examples:

-

In Ukraine, civilians collaborate with the Department of Digital Transformation, using smartphone apps and LTE network towers to crowd-source precise location of Russian ground forces for State air-strikes[3], while the provision of the Starlink satellite system comes at the cost of unexpected outages over funding issues[4] and the geopolitical whims of its CEO[5];

-

Warring countries suffering enormous and disruptive network attacks that bring down civil services, or result in massive data leaks. Russian sanctions remain brutally effective in unexpected ways, such as the withdrawal of Apple Wallet integration in the Moscow Metro ticketing system leaving commuters unable to legally board public transport[6]. In other situations, ransomware attacks now paralyse entire school districts[7] and healthcare systems[8];

-

In Afghanistan, biometric databases myopically set up by the US occupation forces to prevent aid or financial fraud were seized by the Taliban and will be used to track political opponents[9];

-

In Europe and North America, instability around energy infrastructure threatens rolling blackouts and non-functioning public or corporate services;

-

In the United States, ongoing deterioration of the political order leading to the prosecution of teenagers seeking abortion, aided by messages turned over from social media to oppressive law enforcement, as well as the very tangible fear that menstrual cycle apps will be used to track and criminalise sexuality and bodily autonomy in a post-Roe vs. Wade era[10];

-

Internationally and online, the continuing rise of substantial international harassment campaigns, often targeted at public or political figures from under-represented minority demographics.

Each of these examples represent a local or global flashpoint facilitated by the design decisions of a complex, interlocking software and hardware stack now under pressure from external forces. Despite an increased awareness of the manifestation of digital infrastructure, the attitudes of tool builders, policy makers, and infrastructure designers have not kept pace. Many of the unintended consequences of digitisation are the result of weaponised design[11] a process in which a system or interface harms users while behaving exactly as intended. As an umbrella term, weaponised design identifies shortcomings of bias, poorly considered trade-offs, and undeserved placement of trust in organisational behaviour as key causes of harm, and points to broader gaps in policy and practice that paralyse attempts to confront the consequences of digital infrastructure design. Key to understanding this is the unwavering belief by tool-makers, security researchers and other technologists of the inherent integrity of their work within a compromised system.

The disconnect of practice from material conditions is accelerating thanks to a generational narrowing of perspective of systems designers caught in the vice-like grip of the doctrines of scale and cybernetics. The a priori belief in the self-sustaining nature of such technical systems, borrowed from the study and purposeful destruction of ecosystems by colonial scientific ventures, informs much of the blinkered understanding powering the fields of cybernetics. This legacy influences ecology and the entirety of contemporary technology[12]. A rationalist systems approach to digital practice cultivates a feedback loop where the solutions offered to solve structural harms create new structural harms. While the intentions of practitioners often come from a sincere desire for intervention, these interventions themselves risk cascading second and third order effects. Those who bear the brunt of future harms are often already marginalised and disenfranchised by the very technology systems now deployed to produce new solutions. Examples of this include:

-

The never-ending cat-and-mouse game of personal digital security, where individuals must be trained in unfamiliar rituals and technology to defend themselves against their own personal devices;

-

The ethics-led 2010s activist movement that highlighted racial bias in machine vision, resulting in the proliferation of violent surveillance systems targeted at minorities who had previously failed to be recognised by biometric systems[13];

-

The ongoing futile attempts to develop ethical digital consent where users are asked to provide informed consent to data sharing in incomprehensibly complex networks of relations and actors[14].

While much work needs to be done to bring broader awareness of the shortcomings of the practices of tool and infrastructure building, momentum to address these problems is growing. Re-thinking assumptions around infrastructure scale, challenging the storage of user data, increasing awareness of socio-technical security[15] and efforts to embrace — rather than erase — the complexity of digital systems all represent tangible threads for which an alternative and more resilient types of digital tooling may emerge.

Digital archiving is the practice of collecting and/or digitising, cataloguing, storing, curating, navigating and retrieving cultural or historical material for preservation, using computers and other digital or electronic systems. Digital archiving is a computing discipline with a number of unique complexities. The practice borrows heavily from its academic equivalent and draws its definitions of collection, curation, preservation and storage from historical practice. At the same time, digital archiving is both enhanced and affected by digital systems. Digital archiving is not always focused on safekeeping digital artefacts, digitisation of physical ephemera is just as important for the practice. The digital aspects of digital archive have particular influences on the practice through methods of storage, implications of privacy, the challenges of digital resilience, material accuracy, fidelity and other factors.

Web archiving is a subsection of digital archiving and preservation, where the focus of archiving is contained to material available on the internet. Web archiving remains a niche discipline but is a profoundly important one. The preservation and curation of web-based material for cultural, legal or historical reasons can be just as crucial as its physical equivalents, although the expectation surrounding the temporality of internet content remains hotly contested. The United States has produced the majority of attitudes and practices towards digital archiving, driven by state actors (e.g. the Library of Congress), publicly funded institutions (e.g. The Smithsonian) and larger non-profits (e.g. the Internet Archive) and their supporters (e.g. Electronic Frontier Foundation). Also playing a major role is a selection of European counterparts, with major contributors hailing from Germany, Denmark, Holland and the United Kingdom amongst others.

The landscape for web archive tooling is small. Tools are resourced either by a handful of primarily US or Western public or political interests, supported through voluntary or grassroots open-source projects, private endowments, State apparatuses, art institutions, or — more recently — through successful cryptocurrency speculation and capital raising. Each of these sources have distinct clusters of social motivations and expectations of what an archive is and how they are created, curated and maintained. Incredibly, almost all archival efforts rely on just a handful of base tools to capture and maintain their collections.

Commercial digital archiving storage software is almost always inappropriate for their advertised purpose. Open-source archiving tools and systems often require large topologies of infrastructure and specialised expertise to create and maintain, and their commercial counterparts provide products and services to make digital archiving more accessible and cost effective. However, the requirements of archiving and the nature of capitalism present a conflict of interest, where resources committed for preservation are collaterals for profit extraction. If and when a financial agreement ceases between an archivist and a commercial vendor, access to an archive may be restricted or the archive may be destroyed.

This report is part of a material examination of digital archival tools and practice, against the backdrop of a rapidly deteriorating set of global conditions. It is the second publication within the larger research roadmap by New Design Congress, and thus is scoped to web archiving rather than the entire discipline — a framing that provides a necessary focus but also entails limits. Commercial web archival systems are also excluded from this research for scoping reasons, with exceptions made on an individual basis.

At a surface level, web archiving appears to have a simple definition. However, the practice is far more complicated than it seems. Web archives include:

-

Static websites, plain HTML and CSS, and optionally page-enhancing javascript;

-

Complex live-updating web applications (such as social media platforms) that require special tools and significant effort to collect an accurate representation for archival purposes;

-

Audio and video media, including podcasts, streaming services, video sharing sites, etc;

-

Video games, including web-based game consoles, web-distributed video games, distribution platforms, etc;

-

Binary data, such as niche software applications or even malware;

-

Proprietary objects, such as Adobe Flash and Microsoft Silverlight components that require special visualisation in order to reproduce.

Web archives are also often substantially larger than other forms of archives due to the accessibility of web authoring tools, the nature of hyper-linking as a core paradigm of the web, the ubiquity of social media platforms, and the low cost of content creation and distribution combined with the requirement of storing versions of archived material that changes over time. Web archives deal with significant complexity both in their diverse range of preservation objects and the sheer scale of potential archival material inherited from the vastness of the Net.

Web archive tooling is maintained by a small number of entities. The material manifestations of web archiving can be observed through the tools built by these individuals and organisations. One influential web archivist entity is the Internet Archive, a San Francisco-based institution with a significant contribution to the field. Over the past 25 years, the Internet Archive has, in their own words, been "building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artefacts in digital form."[16] The Internet Archive is a widely known web archiving institution with significant influence, whose output includes tools and formats for archiving and digitisation, public access to curated and user-generated collections, and pay-walled archival services that support the organisation beyond endowments and donations.

Because the Internet Archive's philosophies and products are influential, examining its institutional behaviour, its philosophies and priorities, the choices in the design and implementation of its tools, and its history serve as a useful shorthand for illustrating broader strengths and failings within the archiving discipline. This is illuminated in moments where the organisation's ideologies and methodologies clash with the material realities of world events, create uncertainty around collaborators' safety, or cultivate tension with vulnerable online communities subject to archiving.

The Internet Archive and its collaborators (e.g. Archive Team) consider the Internet to be of cultural significance, and their prime directive is to preserve as much of its contents as possible. These teams are motivated by a shared perception and ideological objection to the destruction of online material — defined as digital culture — at the hands of corporate decision-making processes or government interests. The Internet Archive will often archive and preserve a particular platform that will soon cease to exist, collect material subject to copyright disputes or censorship, or develop entire large-scale archives during times of real-world state conflict.

In framing their practice through such an urgent lens, where decisions must be made quickly to preserve fragile or at-risk digital culture, the Internet Archive is able to dismiss objections to digital archiving by framing such criticism as not understanding the permanence of the Internet. While this position can often be justified, this urgency also helps drive the development of tooling and infrastructure using approaches that do not account for the agency of individuals and communities subject to archiving. The most basic example of this is the practice of ignoring a site owner's robots.txt file — a ubiquitous way for system administrators to express consent by explicitly asking autonomous programs not to archive a particular site[17]. Archive Team co-founder and Internet Archive software curator Jason Scott describes their work as motivated by a shared sense of powerlessness against digital rot:

"It's not our job to figure out what's valuable, to figure out what's meaningful. We work by three virtues: rage, paranoia and kleptomania."[18]

While there is tremendous value in capturing a working copy of the Internet, this is an uncompromising and hardline stance driven by ideological opposition to censorship and corporate platform economics. The simple act of indiscriminately ignoring the directives described in robots.txt, regardless of justification, can also be interpreted as disrespecting the wishes expressed by system administrators to withdraw consent and who do not wish their systems to be archived.

An example of the tension between the archiver and archive subject consent can also be seen in Archive Team's rapid archiving of LGBTQ+ communities during the deplatforming of 'adult content' by Tumblr in 2018[19]. Motivated by a sense of urgency in the face of real permanent data loss in the aftermath of Tumblr's policy change dictated by their then new parent company Yahoo, the Archive Team crawled hundreds of thousands of potentially at-risk user blogs, only deploying an opt-out consent system in response to outcry from their practice. When criticised for this indiscriminate practice, both in this context and others, a common justification for this approach to archiving is that a subject of archiving ought to understand that the "Internet never forgets." If a queer person does not want to be absorbed into a permanent institutional archive, they must not participate in sexual or gender politics online.

It is in this divergence of understanding of networks and the response of the archiver that a key example of the tensions of web archiving are best illustrated. The user-perceived impermanence of Tumblr or an overwhelming desire to participate in a niche culture through the network effects of a social platform, combined with a shoot-from-the-hip approach to user consent during archive practice shares historical parallels with organised institutions forcefully archiving disempowered or vulnerable archive targets. The late-stage roll-out of an application process to allow users to opt out of the archive effort saw potentially vulnerable users navigating a system they did not fully understand — if they had any knowledge at all that they had been subjected to web archiving from a large institution. In acting radically against a corporate vandal, the treatment of its targeted queer userbase and dismissal of their concerns frame the targets of archiving as complicit collaborators with the archivers' capitalist opponent, rather than a disempowered community caught between conflicting ideologies.

In August 2022, Twitch streamer Clara "Keffals" Sorrenti was 'swatted'[20] by far-right reactionaries for her work as a transgender activist antagonising against the rapidly deteriorating climate faced by sexual and gender minorities in Western societies. This was not a once-off event: the act of leveraging an individual's personal information to coerce hyper-militarised police squads into performing violent raids on harassment targets is a deplorable reality of the internet. For Keffals, this act had been perpetrated by members of KiwiFarms, a far-right forum whose users engage in brutal harassment and surveillance campaigns against outspoken or visibly online minorities. In response to her personal information being posted on the KiwiFarms forum, along with libellous and unsubstantiated claims made against her character, Keffals used her public visibility as a Twitch streamer to launch #DropKiwiFarms, a grassroots campaign to pressure infrastructure resilience service provider Cloudflare to drop KiwiFarms as a customer. Despite the latter appearing to violate Cloudflare's Terms of Service, Keffals and her campaign team had to endure weeks of escalating threats to their personal safety before the company withdrew their protection of KiwiFarms.

As the organisation's tools had been used to create an archive of the site and personal information of targets, the Internet Archive faced calls to take down their KiwiFarms archive. In the political effort to dismantle KiwiFarms as a far-right political agent and hate group, the Internet Archive was presented with a situation that contradicted the institution's political convictions. Having provided archival mirrors of the entirety of KiwiFarms that included personal information of political targets, the Internet Archive reacted by removing access to their archive of the KiwiFarms site after Cloudflare's decision. While this was undeniably the correct decision, in doing so, the institution had unwittingly become the agitator in their own ideology, a destructor of internet culture facing criticism of 'erasing' a historical event[21].

The claim that the removal of KiwiFarms from the Internet Archive has a chilling effect on censorship or the integrity of internet history is completely baseless, and the Internet Archive was right to move swiftly to remove the archived site. However, the argument opposing the Internet Archive's actions subtly leverages a key ideological distinction found in all colonialist archival systems: that the only valuable memory of record is one that captures an accurate 'apolitical' and unmodified representation of a historical context. As Hong Kong philosopher Yuk Hui points out,

"The will to archive turns archives into sites of power. Besides the dominant narratives set up in the archives, we can also observe power in the relationship between institutions and archives. Each institution has its archives that contain its history and discourses. In order to maintain its status quo, each institution needs to give its archive a proper name […]. An archive is also a symbol of authenticity and authority — a monument of modernity."[22]

The ability to govern, modify, authenticate and destroy archival information raises complex questions around censorship and data resilience, but also user and curator safety. These additional questions are often ignored or downplayed. While the Internet Archive is able to accomplish the takedown of violent material through its governance, other archive and preservation projects cannot. The Inter-Planetary File System (IPFS) is a decentralised protocol that, in their own words, "preserves and grows humanity's knowledge by making the web upgradeable, resilient, and more open."[23] First released in 2015, IPFS is a sophisticated protocol for distribution, authenticating and storing data that can be accessed using methods that, to users, feel familiar to common methods of file or web-browser access[24].

According to the project's website, one of IPFS's use cases is to provide resilience and permanence to an impermanent Internet[25]. IPFS maintains access to data via decentralisation, where data is replicated across multiple custodians for redundancy and resilience. In order to ensure that the distributed data is not tampered with, IPFS leverages a form of immutability, where data cannot be modified or deleted. All modifications to IPFS content is instead versioned. In an era where democratised access to communication and knowledge clashes daily with censorship and information warfare, the need for data resilience in a generally untrusted and ungoverned distributed network of custodians is obvious. Enforcing transparency and versioning creates a system of accountability for network participants. But this is a hardline stance towards data resilience that has immediate and under-acknowledged real-world implications.

In the case of KiwiFarms, IPFS could have theoretically been deployed to assemble an undeletable archive of the site. This would result in a catastrophic permanent repository of personal information collected with the intent to harass and intimidate. The exploration of resilient protocols like IPFS by far-right actors whose internet presence is in the process of being deplatformed is not new. In 2019, an Australia-born fascist posted a manifesto and livestream link to the far-right 8chan message board before murdering 51 people in Christchurch, New Zealand. In the subsequent blowback to the atrocity, the administrators of 8chan openly explored data permanence options[26] — including IPFS, peer-to-peer protocols and blockchain projects — as they raced to subvert the takedown of the site.

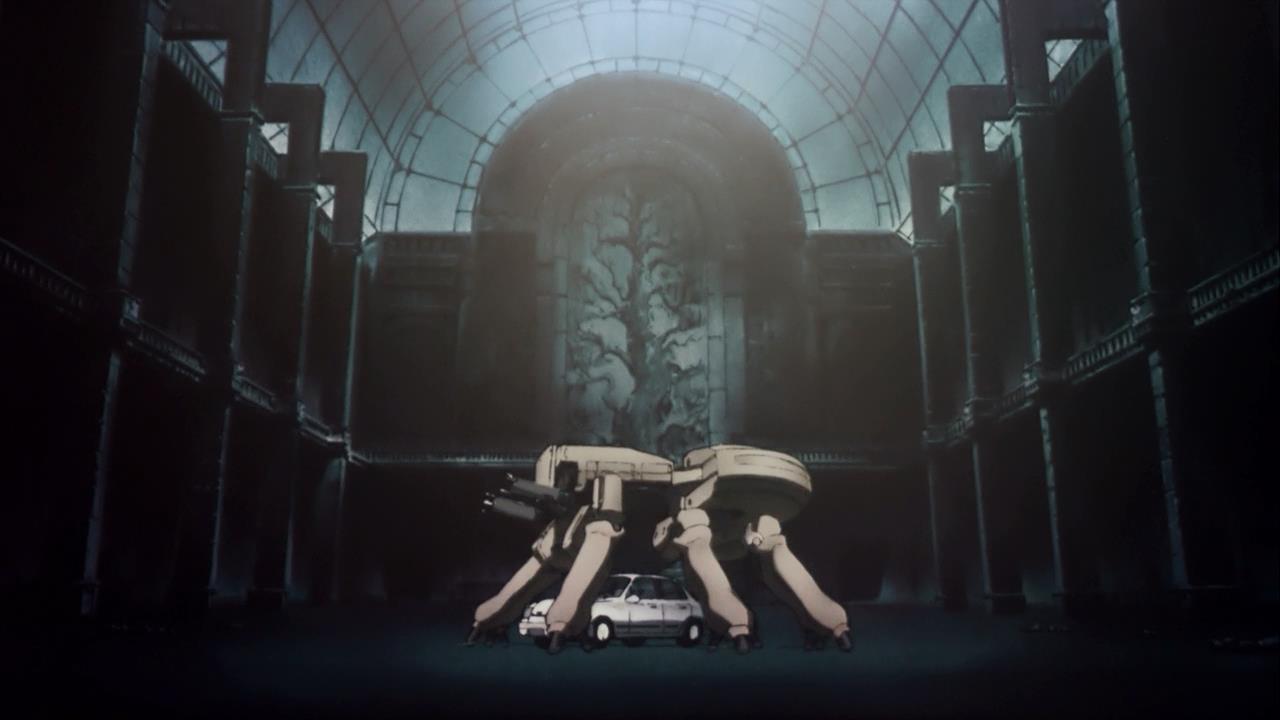

For KiwiFarms, the removal of the site from the Internet Archive spurred the forum members to begin creating their own archive of the site. KiwiFarms members had already published how-to guides for using tools that can be operated by individuals rather than relying on institutional services to produce an archive. The constant risk of deplatforming experienced by far-right operatives has driven its proponents to examine alternatives. As KiwiFarms faltered, its members shared advice for operating archival tools to preserve the site. Among the recommended tools was Webrecorder. Webrecorder is an open-source suite of tools that is capable of producing high fidelity portable web archives via user friendly browser plugins and automation software. For KiwiFarms, Webrecorder was one of a suite of emerging tools that provides local-first archiving free from control by institutions. Some users were already familiar with the open-source tool because, in one sense, Webrecorder offers its users the ability to route around the established relationships between institutional service providers on one side and users, communities and other entities that rely on digital infrastructure on the other. This is an ideology that is rising in popularity thanks to increased awareness of the implications of surrendering agency to platform owners in exchange for convenience or access to digital products and services.

For tool makers providing platforms for archive and preservation like Webrecorder, the complexity of responding to users' needs is heightened by the fact that providers cannot look, 'physically' or ethically, into these users' archives. In our research, a participant recounted an unexpected question from a user:

"There was one user asking 'How could they sort my collection of porn videos by the age of the actors?' We really had to think, what are we doing now? Do we even reply to this? Or do we look into this person's materials? Legally, if you don't know what someone is doing on your platform you are also not responsible for it. If you have no way of knowing, you're not responsible for it. There was another time when there was a pull requests to our open-source project: a very small pull request about some visual cosmetics. When we did due diligence on that user, we quickly discovered they were an outspoken neo-Nazi."

Stories of surprised open-source developers encountering reactionary forks of their livelihoods are also common:

"Around 2017-2018, someone forked the DAT project/DAT protocol, the Beaker browser and a whole bunch of other tools and basically made a far-right clone of all of them. And all they did really was just rebrand the entire thing as a singular fascist project… the guy was bothering all of the DAT people in that in that sort of Pepe style, alt-right kind of way. Just a really uncomfortable, kind of low key scary but not threatening. Just like 4chan trolling."[27]

Whether driven by desires for self sovereignty, real or perceived privacy benefits, bad or traumatic experiences at the hands of a platform owner, or something else, on-device or self-hosted alternatives are both increasing in popularity[28] and becoming more accessible to non-technical users. Given that the far-right are amongst those who experience acute platform instability, they often act as a canary in the coal-mine, seizing the movement for alternative self-determined products and infrastructure to pursue their agendas uninterrupted.

In an expert interview live-streamed as part of research into infrastructural colonialism by New Design Congress in 2021, digital artist and Black trans activist Danielle Braithwaite-Shirley detailed how privilege constrains the potential of digital infrastructures. To paraphrase her words:

"In an alternative history of the development of video game technologies, what would game engines had look like had they been built and controlled by under-represented demographics, whose aesthetics and relationships to computers often differ substantially to the privilege of the male-dominated field of the time? What features, graphic options and interactions were left behind due to the identities and material realities of those who created them?"[29]

Braithwaite-Shirley is far from the first to condemn the narrow conceptualisation of infrastructure developed from privilege and safety, and despite speaking about the niche of game engines, this provocation transcends disciplines. For web archiving, this should be considered through the Internet Archive's role as an archival practice facilitator, Webrecorder's role as a democratising force for practice and portability and IPFS's role as a kind of archival venue or storage warehouse. The Internet Archive's ideology of digital permanence and belief that free digital culture is under threat, and Webrecorder's belief in democratic, portable tools informs how they build their tools, who archives, how they do it, and what archives these tools then create. For IPFS, it is the uncompromising devotion to enforced distributed ownership and immutable data that informs who can participate in a distributed archive and the safety of who and what is archived in perpetuity. To operate indiscriminately is to operate from a position of power. The negotiation of ideology that becomes baked into tools via rules and assumptions falls to those who have to grapple with the consequences of archiving, not the tool-makers themselves.

As noted earlier in this report, it must be clearly understood that the purpose of examining the Internet Archive, Webrecorder and IPFS is not to single out these projects and institutions for criticism as bad actors. Each of these institutions have made significant, unique contributions to the capability, accessibility and resilience of digital culture preservation at curatorial, technical and infrastructure levels. Each of these examples also exhibits unique constraints due to their respective nature: Internet Archive is an institution, Webrecorder is a small open-source tool project, and IPFS is a large open-source protocol developed by a private entity. Their contributions have shaped social and technological perspectives for data permanence and access, and have helped to democratise web archiving. But as global political stability unravels, these institutions also act as representatives of the manifesting issues of power and privilege, where their ideologies influence tool design, custodianship and curatorial practice. These ideologies are not shifting in line with the broader currents of the world. The criticisms examined here can be applied broadly to the practice of web archiving and act as a shorthand to understand a set of first principles that are common across web archiving practice.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is little publicly available research or critical evaluation of the existing beliefs and practices of web archiving and how they manifest consequences for those who are involved with, subjected to, or interact with the web archiving process. In the broad landscape review conducted in late 2021, the majority of existing research focuses on digital security or data integrity, colonialism in digital archiving, the user experience of tools, or the political or philosophical underpinnings of digital archiving practice. This report is a wide inter-disciplinary assessment of the realities of web archiving. This research aims to define and explore the gaps that exist between the principles of tool-design in web archiving, and the shifting political realities that provide existential challenges to these principles and their manifestations. ?

II. Research methodology

This research was commissioned in December 2021 by the Webrecorder open-source project with the immediate goal to help the project inform the Web Archive Compressed Zip (WACZ) format and the user experience of the Webrecorder collection of tools.

Following a landscape review, the researchers undertook an internal threat modelling exercise with the Webrecorder team to develop anti-user stories. In digital software design and development, a user story is "a very high-level definition of a requirement, containing just enough information so that the developers can produce a reasonable estimate of the effort to implement it."[30] In most cases, users are grouped through shared socio-economic or biographical data, by their chosen devices, or by their technical or cognitive abilities. An anti-user story is a user story that anticipates unintended or unwanted requirements of attackers — users who intend to weaponise the design of the digital product to inflict harm on others. In information security, the practice of threat modelling would parallel an anti-user story. In this case, the user and anti-user stories were developed specifically for Webrecorder tools and the WACZ format, and covered opportunities and threats related to functionality, interface, integrity and privacy. The user stories and anti-user stories were compiled on the Webrecorder specifications GitHub project[31].

The questions that emerged through the landscape review and user/anti-user stories were divided into key areas of focus:

Identity & structures

- What are the use cases for web archiving in the 2020s?

- What kind of individuals are involved in the broader landscape of digital and web archiving in the 2020s?

- What are the motivations for archiving material via digital methods? Have these motivations changed since the last decade?

- What roles do organisations and institutions play in shaping the policies, dynamics and outcomes of archiving?

- What are the historical criticisms of web archiving?

Socio-technical security

-

What are the overarching threats…

a. …for archivists?

b. …for custodians?

c. …for individuals, communities and organisations subjected to > web archiving?

d. …for viewers, both in their access of and perceptions formed > by a web archive?

e. …for archive tools and formats?

f. …for the archive itself? -

How are web archiving tools vulnerable to weaponised design?

-

Are currently understandings of baseline risk acceptable? If not, can baseline risk profiles be developed?

Permissions & connectivity

- How do networked web archives fit into the use cases identified above?

- What opportunities and threats emerge as an explicit property of decentralised or resilient networked archives?

- What permission patterns can be identified from a deeper understanding of the topographies of archive network types or information architectures?

- How do permission systems dictate the topographies of networked archives and help or hinder collaboration between or within archive teams?

Integrity

- What opportunities and motivations exist for validating the integrity of an archive?

- How do these identified cases change when the archive is replicated or decentralised?

- When is uncertainty in an archive's integrity important?

- What relationships exist between chain of custody or archive governance and archive integrity?

- How do archives influence comprehension? How can this be manipulated?

Navigation

- How do current human-computer interaction patterns and/or user experience paradigms assist or hinder large-scale web archives, from the perspectives of archivist, curator, audience and attacker?

- Are there opportunities to develop new paradigms for navigating web archives?

- What opportunities exist to improve accessibility for creating and navigating web archiving tools?

Agency

- What are the implications of user identity within a collaborative networked web archive?

- Are there opportunities to implement alternative identity paradigms?

- What risks exist specific to personal identifying information (PII) captured inside a web archive?

a. Self-doxxing e.g. by an archivist

b. Regulatory concerns (e.g. GDPR) - Do opportunities exist to design user agency paradigms into archive tools and systems and/or their formats?

In December 2021, the researchers published an open call for volunteers to participate in qualitative research interviews that explored the key questions posed by the research. In order to be selected to participate, applicants needed to fulfil one or more key criteria. Applicants needed to:

-

Have participated in the practice of web archiving, either actively or historically;

-

Be a member of an institution or collaborated with others in their archival practice;

-

Hold an occupation as an archivist, journalist, activist or researcher;

-

Be a member of a community that had been subjected to archiving;

-

Had familiarity with digital archiving tools of any kind.

The open call for participants was circulated through the researchers' networks, and further circulated in adjacent communities. Significant efforts were made to ensure diversity of gender and sexual identity, race, cultural, and socio-economic status. Efforts were also made to ensure institutional archiving participants were not overrepresented in the study. Specific aspects of the global situation presented significant challenges to ensuring broad representation. These included:

-

The COVID-19 pandemic and participant burnout, particularly amongst minorities or in communities experiencing instability or deteriorating safety as a result of the pandemic;

-

The February 2022 invasion of Ukraine driving efforts to preserve Ukrainian culture and support the documentation of propaganda and news events;

-

An acceleration of information warfare experienced over 2020-2022 leading to decreased availability from archivists;

-

Wider global economic instability that had real or feared impacts on practitioner livelihoods.

The majority participants were archivists, researchers and academics, and a minority held roles in the tech industry, the arts and the broader civil society constellation. Similarly, Western viewpoints were over-represented, with well over two third of the participants living in, or nationals of, Western countries. Most — but not all — participants identified as cisgender women and men, with an overall balance in representation between the two. This categorisation remains a simplification for expediency and the security of participants, and does not hope to provide any precise metrics beyond pointing out certain biases in the research. It also doesn't reflect the individual heritage of each participant and its associated influences. The surfacing of such complex interplay of identities, origins and intersectional interests remains the role of the interviews and the subsequent report.

The research interviews were conducted between January 2022 and May 2022 via platforms selected individually by each research participant and facilitated by two researchers — one acting as the interviewer, and the other supporting and note-taking. The interviews were recorded locally by both researchers using OBS Studio, avoiding cloud-based recording features available in services such as Zoom and Jitsi. Although interviews were conducted via video, only audio was recorded. Participants were asked to consent to the interview in advance via the Research Consent Form (see Appendix A).

The research interviews were 90 minutes in length and structured via a series of key questions that reflected the broader research questions (see Appendix B). Participant responses guided the direction of each interview, and the key questions were not always followed sequentially. Recordings of each interview were transcribed and anonymised, before being synthesised as part of the research findings. As per the Research Consent Form, each participant has been offered the chance to review their contribution and withdraw or affirm their participation consent before publication. In the interest of disclosure, one participant withdrew from the project after their participation and their contribution has been removed. The original audio files were destroyed at the conclusion of the research project. ?

III. Key findings

The broad but flattened definitions of archiving

The definitions of web archiving are not settled and expectations vary wildly across cultural and professional lines.

Some web archives are political in nature and contribute to the empowerment of social and political minorities as a form of social history. This is often a second-order consequence of digital colonialism, where market control of the digital public square has been captured by a handful of companies, whereupon communities are not familiar with any alternative. The political nature of this is deeply kinetic, manifesting as temporal digital records of fast-moving real-world events, as well as the 'rehydration' of social media, where the posting of content on social media and subsequent reactions recording in an interface can be replayed and interpreted. In a key quote from a large temporal archive project, a participant reflected that "we were kind of inspired from the whole Black Lives Matter preservation team on Twitter." Other archives are broader and slower in nature, consisting of multi-decade web histories. Sometimes, the curators of archives are more tolerant to graceful degradation, broken components that relied on obsolete web technologies or long-gone server-side rendering.

No matter the type of archive, the role of integrity, accuracy and fidelity are hotly debated. One school of web archiving holds as paramount the ability to fully replay a website, including every interactions of the original site. This perspective considers not just the content, but the functionality and fidelity of the archive collection as being essential to an archive being accurate. A second school of thought sees this philosophy as misguided. Driven by concerns around privacy, material density, technical limitations and the colonial nature of the source of truth, the historical accuracy of the archive becomes dependent on both the capture and the custodianship of its contents.

We encountered no examples where the expectations of an archivist matched with what an archival tool could offer. Archivists described how their tools created limitations to their philosophical understanding of archives. Beyond archive crawl accuracy and replay, these limitations were also conceptual: current interfaces and digital nature make it difficult to picture a web archive in one's head, compared to a physical archive. In more than one case, participants described the interface dissociation they felt in their attempts to conceive of or rationalise their work: "I know 17TB is a lot, but I don't know how many books that is, or how linear feet that is? What kind of building is my archive held in?"

The user experience of digital platforms themselves also plays a role in the flattening of an archive, particularly when content and interface become entangled such as in a web archive. For web archiving, both the web content and the interface that services the content must be archived. This is significantly different to other digital archives that display their collection with a clearer distinction between material and medium. In an accelerating era of engagement, rich interactions that certain types of material depend upon are often reproduced in an incomplete or broken way. This is especially true in temporal material, such as Instagram Live videos, Twitch streams or Snapchat messages, where impermanence and editorialisation are key. In these instances, the definitions of web archiving stand in direct opposition to the philosophical nature of this ephemeral material:

"Web archiving is predicated on some assumptions that are 10+ years old now. There really needs to be a re-imagination of what web archiving is, should be, can be, will be."

Archive complexity is overwhelming

"It feels like the whole archive is akin to a lake, we are kind of giving multiple entries into the lake. But while material can flow into and fill the lake, you can't then draw from it. We don't have a way to do that."

The experiences related to configuring, crawling, curation, taxonomy and validation are universally overwhelming to technical and non-technical archivists alike.

Some of the challenges faced by practitioners are caused by the necessary reliance on multiple tools to crawl and collect material for an archive. Differences between the tools and their outputs mean that archivists have to develop specific methodologies for individual tools and the mixing of different tools. While this might be appropriate for configuring a tool for crawling or contributing to an archive, a lack of output standardisation creates substantial complexity that archivists struggle to overcome. Archivists however must rely on multiple tools to cover their respective shortcomings or the priorities inherent in each tool.

Multiple participants noted that the field of web archiving — especially institutional archiving — classifies the internet via the URL and time. While some participants have experimented with persistent identifiers[32], the majority of the discipline designs relationships between archived material and institutional governance — or decision-making around archives — through a limited implementation of one brittle identifier (usually a serialised unique identifier), and one temporal identifier (e.g. a timestamp).

This is a practice whose shortcomings Trevor Owens, in describing the relationship between Heritrix's[33] relationship to URLs and time, has highlighted: "[This approach remains] more in keeping with the computing usage of archive as a back-up copy of information than the disciplinary perspective of archives."[34] Although simple, combined at scale the URL and the timestamp create a complexity that, together with a lack of archive standardisation, limits the technical and conceptual pathways for archivists to manage their material.

The complexity experienced through tools by archivists may correlate to their over-reliance on automation and may have reinforced the practice of mass-harvesting/broad-crawling. Thoughtful archiving is difficult within a complex archive system, and in response practitioners err on large-in-scope automated over-collection. The output of this process then compounds the problem of archive complexity. Multiple use cases of Heritrix were given as examples, with a common sentiment being that "the Heritrix model is solely based on automation, and we set and forget. Heritrix really works at scale, but is really sloppy."

Decentralisation as a pharmakon[35]

Despite broad levels of experience around web archiving, there is a serious lack of shared understanding of how material risk affects different individuals or institutions involved in collaborative archiving. The deficit of shared awareness of risks around participation, material custodianship and asymmetrical risk based on socio-political factors is endemic. Introducing decentralised archival storage systems — which has a second order consequence of also decentralising the legal and physical risk to individual network participants — would be a catastrophic action without significant cultural shift and education for the field. Decentralisation itself is rarely accurately defined by its proponents, and it can take many different forms, such as institutions sharing joint custody on a private IPFS cluster, federated public archives, corporate ventures, etc.

Across the field, there is an acute understanding of how participating in the archiving of a social movements or political events can draw attention to archivists and expose them to potential online security threats or harassment campaigns. Participants expressed concerns about the potential to be identified through accidental doxxing — leaking personal identifiable information — during their archival practice, such as one's user profile visible in the archived web content. In cases of decentralisation, the inability to modify or retract published material adds an unforgiving permanence to mistakes made in an archival process of overwhelming complexity.

Beyond the rules around deletion within a decentralised archive, material deletion within digital and web archives themselves is also rare. Many institutional archival projects govern their archives with permanence. Problematic or illegal content is instead marked as inaccessible, creating a 'dark archive.' This can be institutional policy but also dependent on laws regulating the archive that forbid the deletion of material. Combined with dragnet-style automated archiving — a common activity conducted by institutional archival efforts — many potential candidates for decentralisation contain controversial or highly illegal material. At the same time, the field of institutional archiving is both acutely aware of its own precarity in participating or holding risky archives. These efforts may have legislative protection with regards to illegal content, but at the same time, their policies under-appreciate the power they wield when they work with those who do not have the same protections: communities, contractors, website owners, activists, or participating institutional and individual partners. This is a dormant disaster in waiting.

Thankfully, there is a level of understanding of the potential consequences of decentralised archive storage, particularly amongst archivists who represent themselves or community-led efforts to produce archives. Participants who were unable to rely on institutional safety were able to articulate their concerns to varying degrees, with many concluding that "the existing decentralisation protocols are not appropriate for archiving." To quote one participant:

"A big thing about controlling an archive is that you can also remove things. Custodianship means that you have the authority to delete. You have to take responsibility for something and its destruction. None of the decentralised protocols support that."

Tool difficulties affect archive curation and quality

Alongside the complexity of tool outputs, the technical and user experience difficulties in configuring and operating archival tools directly influence archives — from the curatorial decisions made by teams of what to collect, to the fidelity of an archive and the completeness of what is collected. This is especially true in under-resourced or time sensitive situations.

This means that archives are often culturally influenced by these external providers. Web archives are wholly dependent on a constant tensions between the whims of internet technologies and the abilities of tools. Unlike physical archives, where non-technical users can form their own solutions to challenging archival problems, the practice of digital archiving is inherently one-sided through the technical barriers of writing software. This creates a user/vendor relation that is not reflected in other forms of archival practice. In web archives, technical capability of the team and the available tools shape the archive and narrow the team's potential. This was systemic but did not manifest as common patterns. Each team had their own individual difficulties:

"Video is difficult for us to sometimes to capture or to make available. The technological constraints make it difficult."

"The expectation is that web archives are fully interactive replication of the live website. So you can look at a web archive and interact with it as though it was the website on the live web in real time. But we find that very tricky to achieve."

Crawls are often supplemented with data bought from the larger institutional archival efforts or directly from social media platforms. In many cases, participants had accepted the role of external data sourcing via third parties into their practice. Participants were broadly appreciative of these relationships with archival institutions, but concerned about institutional change over time: "What happens after our institutional partner's leadership retires?"

Archive navigation is a key area for future research

There are no common practices for developing usable navigation for web archives, either in the practitioner or public user context. This unsolved problem contributes to significant overhead in labelling, authenticating and working with web archive material, limits the adoption of web archiving tools, and harms the portability and quality of their curation.

Participants described highly personalised workflows for navigating large archives, developed specifically for their team or individual circumstances. An unexpected common technique was the deployment of out-of-band navigation strategies: manual systems such as spreadsheets, paper tagging or other documentation that exist beyond archive tools, operating systems, file systems and web browsers. In cases where navigation was considered a priority, teams had dedicated efforts to maintain an up-to-date taxonomy and navigation structure that was manually updated alongside reviews or additions to the archive. Common assumptions of possible solutions — such as full text search — were rejected by participants as contributing to additional complexity:

"We're looking at search access and how we display information. We can do full text search, but it's not refined. A search term returns hundreds of thousands of results and we still can't navigate them."

Web archive navigation faces additional complexities from the user experience interfaces of the material collected. Websites are often optimised for the business objectives set by the website or platform owner, but these goals are completely irrelevant in an archive context. For example, a social media platform's interface may use user experience techniques to priorities certain navigation pathways or promote specific platform functionality, but these will not work in the archive. In light of this, a web archive has multiple competing navigation systems, one within the archived material (especially with high fidelity, accurate material) and the other made up of the archive's navigation interface itself. This represents a significant and under-researched cognitive load when browsing an archive. Further challenges are introduced from inconsistent functionality due to incomplete or broken interfaces within collected archived material:

"There are only two options available to a user. They can enter the site and exit it via a curator-provided navigation structure, or they could enter via any one individual archive point and then navigate or browse freely on the site. The latter is only possible if the site has been captured in full, and if all the various interactions are available."

To combat this, archivists described many methods. Internally, practitioners often use URL schemas as entry-points into an archive, tracked via their aforementioned out-of-band workflows. To augment public facing navigation, practitioners described processes of modifying or annotating archive material itself, leaving recognisable signposts embedded in archive material to help the browsing public navigate the material or confirm the non-functionality of part of the archived interface. The act of modifying a web archive for the purposes of ad-hoc user experience design has significant implications for efforts to develop cryptographic authentication strategies for archive integrity.

Archive tools and processes reconfigure trauma response

"We don't collect moments of joy really, we collect bad moments. The trauma of working on that kind of material is very, very difficult."

"My workload during COVID tripled. I wasn't even working on a COVID project."

This research was undertaken during a deteriorating period in the early 21st century. The COVID-19 pandemic was well under way, having torn through entire communities and overwhelmed hospitals worldwide in its first pre-vaccine year. Decades of climate inaction had begun to manifest as frequent weather-based disasters. But beyond this, participants had worked on projects that either focused on or had intersected with far-right violence, suppression of Indigenous[36], diaspora, non-Western and minority voices and protest, as well as other major traumatic events. Alongside this, the act of large scale dragnet collection of social media often collects material that has not been subject to content moderation.

Participants who chose to share their experiences with traumatic material spoke with a surprising level of awareness around the nature of the relationship between the archival process, ingestion, taxonomy, and display of material. While the experience of and response to trauma is unique to each individual, tool interfaces played an unexpected role in amplifying or mitigating the potential for harm.

Participants described how automated collection of traumatic material either helped protect them from harm, and conversely overwhelmed others with its volume and how the sheer magnitude of harmful material was presented in the archive interface. Participants described the 'roulette wheel' of suggested taxonomies for material, and the potential for sudden exposure to harm when correcting a material classification or authenticating the accuracy of a piece of archived content.

In all cases where participants spoke of trauma in archival practice, participants referred to user experience flows that either helped them mitigate harm, or — unfortunately more often — they felt contributed to a personal traumatic outcome. In determining what recommendations should be considered as part of this research, there was a surprising lack of applicable prior research into the potential outcomes of interface design optimisations with regards to traumatic harm amplification or reduction.

Beyond the potential of trauma within the archive, participants also described the trauma of understanding the potential or realised weaponised design of an archive, for example in cases where an archive was repurposed to prosecute Indigenous activists. In this case, the framing of the archive as a historical memory had entirely different conceptual meaning depending on the background of the individuals subjected to archiving, many of whom had never needed to consider shared cultural memory as a tool for policing and surveillance:

"I worry that the people that we work with don't fully grasp the idea of data having a potential to be permanent."

One participant described a choice made by an institution to archive the personal website of victim of suicide. The participant described an internal conflict between the institutional mandate to provide 'archival accuracy' against the obvious trauma and deeply personal material. While the tooling made the process of preservation effortless, the larger archival services and tool makers do not fully consider the role of trauma in their practices. The gap in policy, combined with the potential fidelity of archive tools, creates a sort of socio-technical purgatory that can haunt practitioners:

"This person who wanted it out in the world has now passed. This is a document of trauma. What's the right thing to do here? Should it be publicly available, or even be preserved? Who do I ask? Would it be different if a grassroots organisation contacted a site owner, and requested this document be saved? Would they think differently about people accessing this sensitive content they currently hold? I think about this a lot."

Colonial methodology and language narrows archive potential

The archival frameworks of digital and web archiving are cogent with colonial epistemology, who sees itself as the sole judge of what knowledge should be, how it should be done, and for what purpose. The practice of web archiving is descendant from Eurocentric academic practice and as a result, the language, philosophies and set of behaviours have carried over to the internet age unchallenged. This is evident in even the lexicon of web archiving itself, the 'capture' of a web page is an uncritical utilisation of generations of colonialist fascination with the Other, capturing and storing objects far from their context and without the consent of those subjected to the capture:

"Museums are in the capital cities, museums are in the colonial centres, artefacts were gathered and taken away, researchers have gathered data and taken away the concept of archives living in a community."

Participant perspective of archiving was either completely outside of decolonialist criticism or deeply informed by it. Participants that offered decolonisation criticism of archival practice described issues of accuracy, agency, flexibility, resilience, digital safety and curatorial richness. Many of these participants could identify opportunities to improve, iterate or, in some cases, completely re-imagine the practice. No one could provide examples of decolonised archival tools:

"The mental models of the Western archiving discipline is alien to Indigenous communities, a lot of care needs to be expounded in order to not expose them to danger generated by digital media."

Participants who did not reflect on colonialist or power structures inherent in the practice of web archiving were more likely to be involved in archival efforts that had concerning policies or qualities, such as cavalier attitudes to dragnet archival practice, lack of consideration towards archivist and community privacy, or a lack of proactive policies regarding illegal and sensitive content held within an archive.

The colonialist approach to web archiving is an active barrier to producing a new generation of politically-aware tools. Without a direct interrogation led and informed by decolonialist voices, it is likely the next generation of tools will, through the defence structures inherent to colonialism, uphold a set of implementations that broadly influence the practice and continue to narrow the potential for web archives. As one participants warns:

"The granularity of the obsession of finding the most minute details for all things is just part of the colonial life. We're trying to conquer the whole concept of all global knowledge across humanity."

The outcomes of this motivation are already being felt.

Digital archiving is vulnerable to political and ecological threats

The digital archive is a surface of broad political threats, targeted both at those subjected to archiving, and the archive itself. Practitioners and other participants alike described cases of weaponised design, where the implementation and availability of an archive harm communities while performing exactly as intended. Digital archives are vulnerable to attack and weaponisation from harassment operations, where information about an individual or community is collected and re-purposed to fit a false narrative. An example of this is detailed in Part I of this report, where the weaponisation and distortion of personal information of individuals by members of a harassment forum was an active strategy to generate false narratives to discredit political opponents.

The development of material for a political web archive also has potential consequences for archivists themselves. The surveillance-riddled modern internet contains interfaces that can leak personal information and identify the archivist responsible for crawling a site. This can be as simple as being logged into a social media platform and having that user state collected along with the intended material for archive, or an archivist's identity can be derived via careful analysis of collected targeted advertising, social graphs and other metadata.

The weaponisation and political danger of archives must be considered carefully as a key factor in the development of authenticity or integrity systems, as well as efforts to provide deletion-resistant archival storage. A dominant tonality expressed during the interviews was that "it would be so much easier to go other places to find any kind of content you wanted, than to try to use this archive." On the contrary, some voices questioned this diagnostic and raised the very real threats pertaining to the digitisation of archives:

"One person's archive is another person's police dossier. It has to be understood that this is going into an archive, it is just as accessible to a researcher with good intent as someone with bad intent."

Beyond the political vulnerabilities of archives, current approaches to digital and web archiving are vulnerable to ecological and other physical threats to data resilience or network access. This can manifest as policy directive to destroy material unexpectedly during deteriorating political situations, during a change in company or government leadership, or as belligerence between nations and the weaponisation of infrastructure like data centres, companies or backbone networks. An illustration of such vulnerabilities occurred when "the Trump administration removed climate crisis research from the government website, and in some cases destroyed the data."

Threats of this nature often have historical allegories. For example, archives of the colonisation of Kenya, the massacre of the Mau Mau[37] as well as their internment in concentration and extermination camps were burned and dissimulated by the British government[38]. The reality of institutionally-driven destruction of preserved material — both in the present and their historical allegories — is not widely considered. The trend amongst larger institutions and tool makers in this space is to consider their positions as stable, as though digitisation and a surface-level democratic process offer resilience and fortification:

"Do we store the contents on a university server, thereby being under their power and control of what gets added? Do we rely on the good faith of myself or other librarians who could be gone the next day?"

Finally, the rapidly deteriorating climate situation has immediate effects for the resilience of digital archives. An over-reliance on climate-controlled data centres, network disruptions from major climate events, and a lack of portability that makes very large web archives difficult to physically relocate, poses a significant risk that has not been fully considered. One participant, whose practice centred around anti-colonialist resistance, highlighted how geography and politics were intertwined with the resilience of their work:

"Our region will be greatly affected by climate change. We were greatly affected by COVID. Being in such an isolated place puts us in a unique position to consider those challenges."

The threats to digital archives remain underestimated. From the deteriorating political situation in the United States and in other flashpoints across the globe, to the deployment of surveillance infrastructure worldwide disguised as pandemic response, the unjustified war on Ukraine or the deteriorating resilience of data centres to climate events, assumptions around political and physical resilience baked into the design of today's digital archival systems are being tested in real time.

Regardless of their own assessment of personal or institutional risk, participants were acutely aware of the global political climate. From archive resilience, to concerns around documentation and preservation of protest, questions around supply chains, and institutional risk, a recurring observation by participants was a sense that archive systems were vulnerable to foundational assumptions made by practitioners and tool makers. To varying degrees, participants felt that circumstances were changing faster than the practice could respond to:

"The type of malicious actions I think of are less technology-based, but more using social-legal mechanisms. I'm thinking of things like SESTA/FOSTA. I'm constantly thinking about the chilling effect that can be created on people through legal mechanisms towards technology."

Archive integrity systems have unintended consequences

The archiving of a constellation of accounts bypasses the traditional individualist framework upon which most laws in liberal democracies rest upon[39]. In many examples, the fidelity and ease of access of an archive compared to a physical equivalent transformed the material into an extra-judicial surveillance apparatus, where incentivised adversaries (such as police investigators) could account for complexity with human resources[40] and military-grade technology to build cases against targets[41].

As discussed earlier, a common assumption is that large, unwieldy archives are inherently safer due to their inefficiency. Some participants described situations that show that this is a dangerous and unfounded position. Dedicated, well-resourced state actors do not see obscurity or complexity as an obstacle. The potential of useful material for a case is enough to request data dumps that can then be sorted by an archivist via legal coercion, or processed by law enforcement. Archives run the risk of misuse in programs such as the US Government's Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency dragnet, bypassing protections afforded by "sanctuary" cities[42]. Participants also described the misuse of Indigenous, diaspora or social movement archives to identify and police legitimate democratic protest. For a number of participants, these are not theoretical concerns:

"We slowly lean closer and closer to fascism. And that means more and more of the materials in the collection that I have been working on incriminates more and more people."

Archive integrity is often considered essential to fight dis- and mis-information, in open-source intelligence and investigations, and to document criminal activity. Participants were split between recognising the need for authentication systems within archives, and the multitudes of legitimate use cases for modifying an archive after the fact. While the manipulation of archive to re-contextualise material in bad faith remains a significant problem, participants broadly felt that strong integrity or anti-tampering systems within archives could have negative effects on their curatorial responsibilities. Many participants described the question of archive integrity as a social problem and considered the institution as the primary arbitrator of archive integrity.

The interface required for an integrity system would need to cultivate within a user a degree of authority and trust that material is not tampered with. From an information security perspective, the introduction of archive integrity and authentication systems adds an additional attack surface that can be gamed and defeated. Once defeated, the manipulation of a digital archive that is then misclassified as authentic may amplify the effectiveness of the falsification, by decreasing out-of-band checks by users and weaponising material trust cultivated through the integrity interface to produce additional impact.

WACZ is well regarded but remains hermetic

"Webrecorder was a real gift."

"I'm always grateful to the Webrecorder team for their help."

When asked direct questions about their experiences with Webrecorder and the WACZ format, participant responses were overall positive. Many participants understood the role and potential of the WACZ file format, and held excellent opinions of the tools developed by Webrecorder, but overall sensitivity to technical failure or user experience frustrations were amplified by the complexities of web archiving as a practice.

Participants who had actively used Webrecorder are eager to collaborate, finance and support the project. Participants who fell within independent practice or non-institutional demographics described how initiatives like Webrecorder allow them to generate income. By decoupling from cloud or service-based archive tooling models, Webrecorder allows participants to create archives outside the structures of institutions. In parallel, Webrecorder also assists autonomous and community archiving initiatives, especially in instances where participants may distrust an institutional partner, or need to create community-led archives. For example, the Webrecorder tools help with urgent archiving initiatives, and a major effort to archive the digital culture of Ukraine was ongoing for the duration of the research project.

Participants were asked to describe the difficulties they encountered when using Webrecorder software. When recounting technical and user-experience issues, participants were often unexpectedly passionate and frustrated. One major cause of this may be Webrecorder's reputation for accuracy and performance which also relies on manual processes. Archivists use Webrecorder in a more manual fashion to fine-tune an archive where other tools and automated processes have failed, and users may begin using Webrecorder in a more involved way whilst in a more frustrated state.

Another core trigger with user frustration may be related to overarching issues of archive complexity and a growing sense of fragility within the landscape of archive practice. Broader research efforts to understand the complexities of archiving and community discussion, tool modernisation, risk analysis and a degree of political consensus will all improve the practice.?

IV. Analysis of findings

The basic definition of archiving is the "selection and classification of accumulated documents and objects,"[43] the practice of collecting, saving and making sure that materials that have been selected for preservation are accessible and protected in the long term. Archiving involves the identification, assessment and collection of those elements that are deemed of historical interest for future generations. The definition of archiving also encompasses the development of ways in which a trusted repository can be established so that people can access and find the information that they need. This results in custodianship, a complex set ofinteractions and negotiations between different individuals and entities aligned with similar goals, but often with broad interests and expectations of archival practice.

This analysis of findings is a synthesis of the landscape review and qualitative research interviews with archive practitioners. Although originally scoped to the Webrecorder project, this research demonstrates that the issues of ethics, consent, digital security, colonialism, resilience, custodianship and tool complexity are systemic and can be interrogated from an epistemological perspective. All participant contributions are quoted and can be differentiated from other references through an absence of a corresponding footnote.

Philosophies and motivations

To understand how to best design and develop digital tools for a new generation of archival practice, we start with an analysis of the variations in landscape of definitions, philosophies and motivations of practice.

Archive practice is motivated by a variety of philosophical, political and cultural motivations. Some of these include:

-

Cultural documentation of public or state actors,

-

Historical preservation for cultural or public interest reasons,

-

Investigative journalism,

-

Documentation of war crimes or human rights abuses,

-

Indigenous[44] or minority visibility and advocacy,

-

Preservation of material placed at risk from external circumstances that can range from platform closure to destruction during warfare.