[1] Why care at all about the politics and economics of video game engines, a seemingly frivolous and irrelevant technology for many industries? For those without a stake or interest in video games, the engines that make them possible appear as nothing more than tools employed by niche companies to produce entertainment for the young demographics of wealthy economies.

This is a short-sighted perspective on an emerging and critical type of digital infrastructure with broad interdisciplinary application and influence. Evaluated in isolation, the cultural influence of the video game industry is huge. Over the past 20 years, video games have matured into a multi-billion-dollar industry, eclipsing the competing mediums of film and television both in size and rate of growth. Unlike other entertainment industries, game engines are capable of supporting small-scale efforts (indie games) and massive projects (AAA games) alike. This is possible in part thanks to the accessibility of game engines for even inexperienced developers. Issues of distribution aside, today’s game engines enable a democratic and competitive participation in the production of video games supported by a ubiquitous—if flawed—set of marketplaces.

The accessibility of video game engines, combined with their core ability of simulating worlds, systems and rules, has cultivated a broader potential beyond entertainment products. Many of the resilient economic solidarity models we have researched at New Design Congress depend at least in part on game engines as a key component for social organising, presentation, education, or economic or social value. More broadly, game engines have found application in a surprising range of disciplines, including architecture visualisation, cultural archival efforts, visual arts, urban planning and traffic simulation, education and vocational training, academia, pilot training, medical research and transportation.

The world that game engines inhabit is changing rapidly, thanks to trends such as the rise of patronage, the coming end of the personal computer, the artificial push by big tech for immersive digital spaces and the proliferation of climate and pandemic-driven hybrid events in response to aesthetic flattening. These trends, combined with the dual shocks of geopolitical and economic turbulence over the last 18 months, have created an inflection point for game engines and the wider disciplines that depend upon this essential technology category. At a crucial moment for game engines, two of the most influential and widely-used game engine platforms are both vulnerable to today’s challenges. What are these issues, and what alternative engines exist?

The landscape of engines

The combination of permissive licensing, investment in developer-facing workflows and 2D/3D engine flexibility has led to the rise of two influential engines: Unity, developed by Unity Technologies, and Unreal, developed by Epic Games. Combined, these two engines hold 61% of the marketshare for game development. Unreal and Unity power everything from VRChat (the biggest social VR platform), to the Matrix Ressurections Unreal Engine Tech Demo, a cutting-edge Unreal tech demonstration produced in partnership with the Matrix Resurrections film release. Both are flexible, general purpose engines, backed by permissive licensing strategies, allowing them to scale across a broad range of projects of differing sizes, including AAA video game titles, film production, and experimental R&D beyond the realm of video games. Both companies also run Asset Stores, leveraging their immense popularity to help teams shorten their development cycles by buying or downloading pre-built code modules. This strategy has successfully cultivated the entrenchment of both engines in the broader landscape.

Despite these successes, the future of both engines is uncertain. As the game engine becomes intertwined with digital infrastructure, Unreal and Unity face serious geopolitical, economic, and privacy issues that have real-world infrastructural consequences beyond video games. These two platforms are deployed across a rapidly expanding surface of disciplines, applications and products: their vulnerabilities must be understood and mitigated through the cultivation of alternative technologies.

Unity’s disunity

In mid June 2022, following rumours of downsizing across the 5,000 strong company, Unity CEO John Riccitiello internally re-assured employees that the company was in good financial shape with no layoffs planned. Two weeks later, the company laid off 4% of its workforce. The move to downsize seemed to be at odds with increased competition in the sector, the widening adoption of Unity beyond gaming, and the upcoming VR/AR wars between Meta, Apple and Valve. But the delivery of a four-year long covert internal project to restructure and rebuild the company’s advertising department was perhaps a key factor in this news. Under Riccitiello’s leadership, Unity was to pivot.

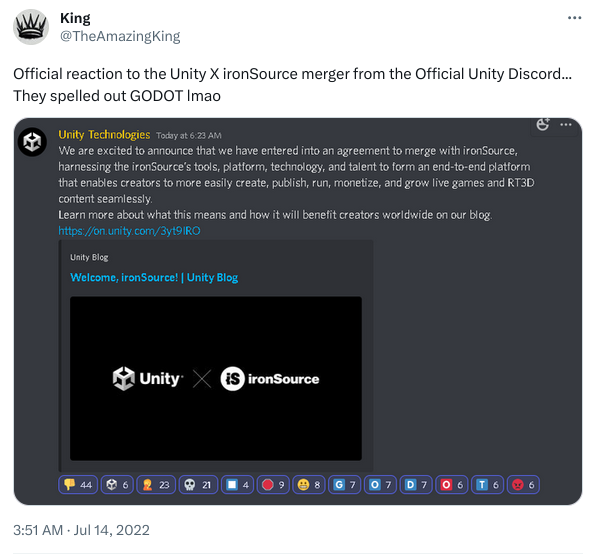

Barely a month after the major restructuring, Riccitiello announced plans for Unity to merge with ironSource, an ‘app-monetisation’ platform. This merger would narrow the game engine’s focus to use cases that prioritise micro-transactions, data collection and paywalls. In their announcement, Unity’s public relations office describes the merger as an opportunity for “creators” to: “leverage data on audience feedback to improve content from the earliest stage in the creation process, and throughout the content lifecycle. This will unlock a flywheel where data from growth feeds improvements in content which in turn drives more business success for the content or app.” Riccitiello's new strategy undermines the broader user-base, potential and use cases made possible by Unity today. Framed within the narrow context of a game engine for independent creators, the strategy integrates user surveillance into the most popular game engine on the market. Given that Unity is used in projects far beyond this framing, the strategy has significant consequences for the viability of the engine.

Unity’s new partner, ironSource, is well known for its advertising and monetisation technology, installCore. Designed to be imported into desktop applications for Windows and macOS, installCore’s invasive design and vulnerable codebase led to the software – and third party applications that integrated it – being classified as malware by anti-virus vendors, including Microsoft’s own Windows Defender. installCore was supported for nearly a decade, and was only discontinued in 2020.

In August, Unity received an acquisition counteroffer from AppLovin, a data-broker competitor to ironSource. AppLovin’s CEO, Adam Foroughi, openly described the acquisition as a direct response to the proposed ironSource merger, and the proposed terms outline the termination of the ironSource merger as key to the deal.

Regardless of which merger strategy is pursued, the decision by Unity’s leadership to merge with an advertising company – one of whom shipped malware to users for nearly a decade – is a significant and alarming diversion from its previous public roadmap. This strategic shift has been met with widespread condemnation from customers and shareholders alike. This ad-based strategy is also risky—Riccitiello joined Unity in 2014, having resigned from Electronic Arts for poor performance after implementing similar strategies.

Unity represents the largest single game engine in terms of marketshare, application and adoption. In 2022, its future is uncertain and focused on a pivot headed by a corporate leader who had demonstrably failed in similar roles with similar strategies. More worryingly, in an era of unprecedented US domestic and international belligerence, this repositioning by company whose products are installed on millions of devices – from smartphones to medical training programmes to electric cars to military use – is a direct move into data-brokerage and surveillance. Organisations and companies outside the United States hoping to incorporate game engines into their work must evaluate this new development as a major threat to a project’s digital integrity.

Unreal’s political reality

Although Unreal commands a significantly smaller marketshare than Unity, it nonetheless remains the second largest commercial game engine platform. Unreal enjoys significant cultural mind-share thanks to innovations around photo-realism, physics and world simulation, real-time performance and developer workflows. Like Unity, Unreal’s future is also deeply uncertain. Whereas Unity’s embrace of predatory economics has seen it emerge as a significant threat with an uncertain economic future, Unreal’s future problems are the result of its broader strategic failures by Epic Games, Unreal’s parent company.

In 2012, Epic Games and Tencent announced a strategic investment, in which the Chinese internet giant acquired 48% of the company for $330 million. This stake was a play at re-configuring the company around Gaming as a Service, favouring iterative releases, continuing revenue and micro-transactions over traditional models for gaming and distribution. It also cost the company leadership dearly. No sooner had the ink dried, several influential staff members departed the company, some citing the new strategic direction as the catalyst for their departures.

The outcome of the Epic × Tencent partnership was the wildly successful Fortnite, the Epic Games Store distribution platform, and ongoing investment in the Unreal Engine. Of these three major efforts, Fortnite’s success generates almost all of Epic’s operating income and profit, thanks to its notorious free-to-play model that deploys unethical dark patterns to solicit micro-transactions and foster game addiction from minors. Fortnite’s success topped $9 billion US, according to discovery documents submitted in an antitrust lawsuit filed by Epic Games against Apple, providing significant capital to support Epic’s other strategies, including Unreal, but hitting the limits of its growth due to Apple’s App Store policies and 30% income-share for in-app purchases.

In a bid to reduce Apple’s cut of Fortnite’s success, Epic’s lawsuit argued that the locked down control of iOS by Apple amounted to anti-competitive behaviour. This legal challenge against Apple’s App Store distribution platform was a strategy designed to legally force iOS open, allowing Epic to further grow Fortnite’s micro-transaction economy and, presumably, expand the Epic Games Store onto iOS devices. Epic’s claims were dismissed, and the App Store remained under Apple’s tight control. Simultaneously, Apple retaliated by removing Fortnite from sale, causing an ongoing decline in players and revenue from the game.

The company’s efforts to develop its Epic Games Store is a loss-making operation, limited to a tiny install base of desktop computers and reliant on significant up-front cash incentives to make upcoming game titles exclusive to the platform. Like Fortnite’s micro-transactions, the Epic Games Store growth is severely limited thanks to the failed Apple anti-competitive litigation. At the same time, it’s biggest desktop competitor, Valve, chose an R&D strategy built on open-source technologies instead of litigation. In the 2010s, Valve released a line of VR headsets, and in 2022 followed them up with the Steam Deck, its own hardware gaming system and a major post-personal computing platform. Like Epic, Valve importantly also owns Source, a culturally significant and extremely valuable game engine IP, alongside a host of valuable game IP — Half-Life, Counter-Strike, Dota, Team Fortress and Left 4 Dead being their most popular. Unlike Epic, Valve has an substantial, forward-looking and ambitious hardware strategy.

Epic’s continued development of Unreal relies almost solely on Tencent and Fortnite. With Fortnite removed from the largest mobile gaming platform resulting in a significant decline in players, a multi-million annual loss from the Epic Games Store, and a lack of short term strategic alternatives, the continued reliance on a video game property whose predatory practices have seen it banned from China and the ongoing focus of legislation elsewhere, Epic’s continued successes are far from certain.

But more importantly, the controlling financial stake held by Tencent creates a dynamic that is wholly dependent on geopolitical relations between China and the US, for which culture and entertainment plays a politically central role in exerting soft power. Should these already-fragile relations sour, Epic’s position as a US-based cultural export and a technology company places it in a unique position for political and regulatory scrutiny, both from the United States and China. The launch of China’s GPDR-style PIPL privacy law and rising tensions between the two super-powers has led to an exodus of US-owned technology companies. If Epic is used as leverage during deteriorating political relations, this would have significant consequences for the future of Unreal Engine.

The possible inflection point

Whether developing a mobile game, building a persistent online world or producing simulations or other research, an alternative solution must be ready for the coming inflection point, where one or both of the two largest game engines become untenable. Fortunately, an alternative already exists – Godot.

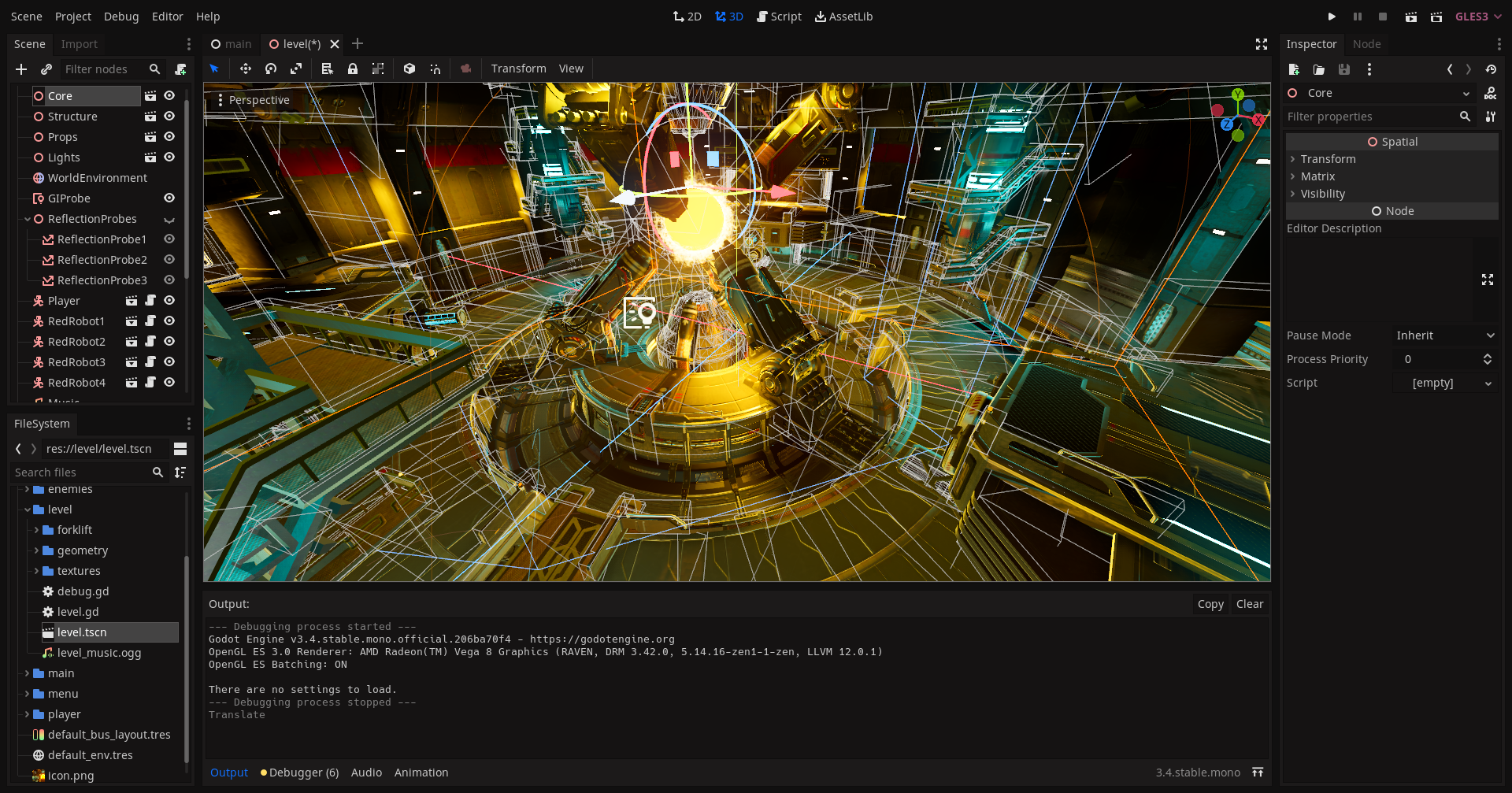

Founded by Juan Linietsky and Ariel Manzur in 2014, Godot is a cross-platform open-source 2D/3D game engine. Godot is positioned in a similar space to both Unreal and Unity, and offers accessible, democratic tools for developing simple mobile games, software applications, and even HUD (Heads-Up Display) animations in electric vehicles. The project has seen broad adoption, particularly in the last three years, and provides the engine with a small but modest number of culturally significant video games released since 2020.

Godot’s fledgling development community, broad application potential and maturing toolset offer a true third party alternative to the Unity/Unreal paradigm. Godot has even onboarded an increasing number of “Unity refugees,” each group arriving in waves that correspond to unpopular updates issued by Unity’s leadership. As Godot is open-source, it can be modified or forked to resist situations like Unity’s proposed integration with ironSource. Although not as technically sophisticated as Unreal, Godot’s financial support is not derived from one of the most successful and predatory video games on the market, and its future does not depend on geopolitical belligerence between the United States and China.

Godot’s powerful tools and open-source licensing do come with drawbacks. For example, Unity’s market position has given rise to the Unity Asset Store, a digital shopfront where development teams can purchase pre-made assets, code modules and other tools that shortcut development time and lower costs. In compiling this research note, we spoke with a number of non-US based teams who are using Godot to develop software tools or cultural platforms. While Godot is supported by a rich range of plug-ins, this ecosystem is not yet mature, and is no match for the sheer size and turn-key potential of the Unity Asset Store. In our research interviews, participants noted that the additional costs for developing sound, video, networking and other components with Godot were substantial. This cost is not offset by the lack of licensing fees compared against Unreal or Unity.

Yet, despite these challenges, the proposal to position an open-source media tool as a viable industry leader is not without precedent. Blender – an open-source 3D modeling and rendering tool – has a similar historical trajectory to Godot’s. Founded as an open-source project in 2002, Blender’s 20 year history is the story of committed community development and strategic investment from both direct partnerships and distributed funding. Following a major UX overhaul in the 2010s, Blender has enjoyed a stratospheric rise to become an industry standard despite hundreds of millions invested annually in competing commercial alternatives. Blender’s powerful modeling and rendering tools and its best-in-class user experience make it incredibly versatile, yet easy to learn and master. Its status as an open-source and extensible project has fostered a blossoming plug-in ecosystem and – more importantly – allows professional teams from a variety of industries to customise and integrate Blender safely into their workflows.

With attention and support from a diverse range of interests, Godot could begin to follow a similar trajectory to Blender. For this to happen, support should extend beyond simply financial patronage of the engine; funders should prioritise proposals or existing projects that use the Godot engine. Educators should consider incorporating Godot into teaching materials, especially in coding bootcamps, game design and other design media courses. Development teams should consider releasing reusable components as open-source assets to help cultivate a supportive Godot ecosystem.

In July 2022, Godot announced a feature freeze for version 4.0, a substantial upgrade to the engine that may be as significant to the project’s adoption as Blender’s UI/UX revision. What’s needed now is broader cross-industry financial and technical support, informed by heightened understanding of the looming political, financial and privacy threats emerging from the commercial heavyweights.

The surface of cultural production remains a key ideological and economic battleground. Game engines remain underappreciated for their cultural and political influence, and their ability to democratise this newer form of cultural production. Beyond their role in entertainment, the use of game engines continues to expand into areas of research, architecture, simulation and other disciplines. The uncertain start to the decade – fueled by accelerating data exploitation and geopolitical belligerence, and crystalised within video game engines – creates a new threat for organisations, researchers and creators that demands a focused strategy to empower an open alternative. With Godot, it is not too late to make this happen.

Title photo: id Software's offices, 1996. id is most famous for its contribution to gaming culture and technological advances in the engines that power them.

John Romero

14 February, 1996 ↩︎Hyper-real computer-generated models of Keanu Reeves and Carrie-Anne Moss developed as part of Epic Games and Warner Bros. Matrix 4 Unreal 5 tech demo.

Epic Games

2021 ↩︎A screenshot of the Godot 3.4 interface.

Click to enlarge ↩︎@TheAmazingKing

Twitter

14 July 2022 ↩︎Blender's powerful interface and rendering tech has made it a leading tool for world-building and democratised creativity. As seen in World Building in Blender

Ian Hubert

2019 ↩︎